Featured image: Jackson Pollock, Lavender Mist

[04.04.2025: I just started writing a follow-up to this post. They are thematically related and I want their titles to reflect that, so I am renaming this from “More Input” to “On the Quantity of Input.” The URL slug shall remain the same.]

[I wrote a post along these lines some years ago. That was more of an extemporary diary entry, while this post has been thought out.]

I am addicted to screens. I am addicted to looking at them and I am addicted to listening to sounds emanating from devices with them. This includes music, podcasts, videos, series and feature-length films. I collectively call this voluntary external input* and generally consume it in conjunction with other activities: when I run, am at the gym, taking a shower, doing chores around the house, cooking, or eating.1 Since my attention is divided when I consume this input, I don’t even take most of it in. The chief purpose it serves is keeping the stimulation my brain gets up to par with the levels it has systematically grown used to over time. Remember this highlighted bit—I will reference it later.

*Detour: A formal definition of voluntary external input.

voluntary external input

noun

Input from external sources that is actively sought out and within one's control.

Examples: a book read, a podcast episode listened to, a video watched

Counterexamples: involuntary external input: traffic noises, an immediate neighbour's phone conversation on public transport, smells upon entering a cafe; internal input: thoughts, reflections, recollections, emotions, imaginationThe fact that more and more of my digital haunts seem to be introducing features meant to cater to my shortening attention span (and to make it shorter still) does not help. Some of these features are: endless scrolling, frequent notifications and pop-ups, personalised content and ads, short-form content, picture-in-picture videos, and autoplay.

Let me zero in on what, in my opinion, is the biggest offender: short-form video content. TikTok has TikToks, Instagram has Reels, YouTube has Shorts… and now even LinkedIn and Spotify have short-form videos. We are getting increasingly used to consuming content in this fashion—in little snippets that are just flashy and interesting enough to hook us in, but not so interesting (or indeed, so long) that they would require any sort of commitment from the creator or from the consumer.

Drew Gooden, one of the few YouTubers whose content I genuinely enjoy these days, put out a video essay about content designed to waste time. The section on social media resonated with me in particular.2 He says…

“There’s this weird feeling I get whenever I go on TikTok or Instagram Reels […] where I’m simultaneously aware of what it’s doing to my brain, but I do nothing to try and intervene. I just sit there and let it destroy me because I have to see that next video. What if it’s so funny but I exit out of the app before I ever get a chance to watch it? […] And it’s almost as if that feeling is intentional. They’ve made it so that the distance between you and a chance at dopamine is just one small swipe away.”

(Media) Overconsumption

Overconsumption has been a topic of significant discussion in recent years. While we only think of it in terms of goods and services, the way we consume media can be considered as overconsumption in its own right. Where one impacts our planetary health, the other impacts our mental and physical health.

I would even make the case that the latter exacerbates the former. The more content we consume on LinkedIn, Instagram, Netflix and so on, the more exposed we are to the thought, “Look at what this person/influencer/character has—it’s a nice thing. You like nice things, don’t you? Don’t you want it? Don’t you need it?” The rational part of you, of course, tells you that you most decidedly do not need it, but because it’s not easy to heed this truth, you might end up purchasing that nice thing.3

Putting Off Thinking

Remember the sentence I highlighted above? That’s the primary purpose of the constant stream of input that I indulge in. Its secondary purpose is to dilute my need for thought. Thinking requires work; consuming is effortless.

And I don’t think I am the only one who does this. I see countless people engaging in similar behaviour every single day, from early in the morning (gym-goers scrolling on their phones between sets), to later in the day (colleagues listening to music while they work), all the way to the end of the day (co-passengers on the S-Bahn reading the news on their way home).

I understand that all content is not created equal; someone reading a book or an e-book on Dancing is admittedly less stimulated than someone rapidly scrolling through dance trends on TikTok. The mental bandwidth taken up by reading still leaves space for your brain to generate thoughts about what is being read. That taken up by fast-moving, flashy, loud videos, however, leaves far less. The more we lean towards input with higher and higher stimulation, the lesser we are able to produce our own thoughts, our own output.

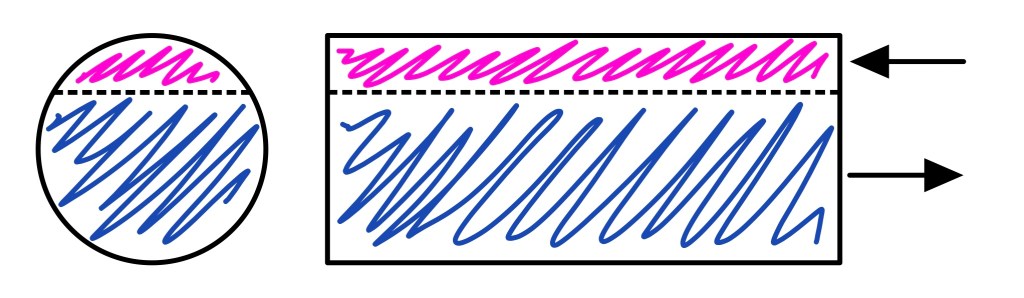

Detour: An illustration to explain my point.

I think of it as a pipeline with a fixed diameter and a movable membrane splitting it into two parts: one part is for the flow of input that you take in from outside and the other, for the flow of output that you produce.

I made some drawings to visualise this: The circle on the left is a horizontal cross section of the pipeline and the rectangle on the right is a vertical cross section. The dotted line is the membrane.

Hope that makes things a little clearer. Now getting back to our disinclination to think…

It’s a vicious circle: You tend to avoid being alone with your thoughts, you consume content to drown them out, it fuels your incapacity for thinking. Rinse, repeat.

Outsourcing Thinking

Now, with the advent of artificial intelligence, we have been able to take this one step further: Not only is it easy to put off thinking, now, we can now outsource it altogether.

The brain is like a muscle… it adapts if you challenge it, it sheds neural connections if you let them fall out of use. Using ChatGPT to help you come up with ideas or to draft an email won’t make you lose your ability to think and express yourself, but what about the ability to think and express yourself well? Is it not equally important to pay attention to the quality of your cognitive output? Does it not matter whether that output is truly yours or not?

In his book, 1984, George Orwell says…

“Nothing [is] your own except the few cubic centimetres inside your skull.”

While the context in which this sentence comes up in the book is completely different, it encapsulates the point I am trying to make quite well: The only things that are truly yours are your thoughts. Granted, they are shaped by external stimuli, they might even be very similar to someone else’s thoughts, but they are yours in that they occur to you. They are original at least on that level. Even my current floundering in my effort to explain this point is individual to me.

Case in point: I am typing this into the text editor built into WordPress. When I hover over a block of text, it shows me a little pop-up for an AI Assistant… Let’s give it a whirl. I will repeat the previous paragraph, but let AI work its magic on it with the prompt “phrase this better.” Here’s what I get:

While the context of this sentence in the book varies greatly, it effectively conveys the point I wish to express: the only things that are genuinely yours are your thoughts. Although they are influenced by external stimuli and may resemble someone else's ideas, they remain yours because they arise within you. At least on that level, they are original. Even my current struggle to articulate this point is uniquely mine.Written very well, but not by me. I would never write exactly like this. I would never say “arise within you,” for example—not even ironically.

I don’t want to make this a diatribe against AI; it has been done before and done well. Though there are plenty of ways in which we can abuse AI, it will be silly not to acknowledge its fair share of useful applications. So I will cut this discussion here and get back to my main point.

My Main Point

Another quote from the video I referenced at the beginning of this post goes as follows.

“I don’t need to min/max content consumption. In fact, I probably shouldn’t be doing that. I don’t think prioritising constant small hits of dopamine, hoping it all adds up to something meaningful, is the secret to being happy.”

Last month, while standing in the kitchen, soaking up some autumn sunlight, sipping my coffee, unaccompanied by any song, podcast or film, I felt like I figured something out. There was a sheet of paper on the counter next to me, which I had been using to jot down and check off the chores I wanted to get done. Before the feeling passed, I made this note at the bottom of that sheet4:

To give you some background on Fenchurch… She is a character from the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams. He introduces her as follows.

“And then, one Thursday, nearly two thousand years after one man had been nailed to a tree for saying how great it would be to be nice to people for a change, a girl sitting on her own in a small café in Rickmansworth suddenly realized what it was that had been going wrong all this time, and she finally knew how the world could be made a good and happy place. This time it was right, it would work, and no one would have to get nailed to anything.

Sadly, however, before she could get to a phone to tell anyone about it, the Earth was unexpectedly demolished to make way for a new hyperspace bypass, and so the idea was lost, seemingly for ever.”

It turns out I misremembered—Fenchurch figured out something, but it might not necessarily have been the secret to happiness. It also turns out that I misphrased my own note—I didn’t figure out the secret to happiness either, but rather the key to finding the calm my brain had been craving. Or so I think. Let me put this to the test.

Self-Experiment

In Deep Work, Cal Newport urges his readers to embrace boredom. He argues that, by training ourselves to get comfortable with periods of lower stimulation without resorting to seeking out external input, we can improve our ability to focus on a single task without the constant need for novelty. In the spirit of embracing boredom, I am going to try to see what my stimulus-hungry, multitasking brain does when I deliberately restrict the volume of input I feed it.

Here are some ground rules—from least to most challenging—that I will follow until at least the end of this year. Once this year is up, I will either continue following them for an indefinite amount of time, make some modifications to them which make them more practicable, or stop cold turkey (the last eventuality is unlikely).

- No social media.5

- Reading physical books/papers/articles is allowed if that is all I am doing.6

- No external input while I shower.

- Watching a video/series/film is allowed if I have sat myself down specifically for that and that is all I am doing.7 This also means no second-screening.

- No earphones/headphones.8

- No carrying screens with me to bed.9

- No external input while I eat.10

- No external input while I train.11

I just realised that this is essentially single-tasking with a few additional constraints. That’s good, now I have something to call this experiment in my head. Some of these rules are rather harsh12, but I feel like I need to jump in at the deep end here. I need to learn to be comfortable with my thoughts and embrace boredom—no matter how uncomfortable that makes me—before I can start giving in to my brain’s need for stimulation. The hope is that this need will decrease the longer I keep at it and will eventually plateau.

I keep harping on that we are what we consume. When I eat ultra-processed fast food, I feel bloated and sick. When I go down a brainless rabbit hole on YouTube, I feel lethargic. When I doomscroll, I feel jaded and hopeless. All of this is to say that the quality of input is important as well.

My experiment only focuses on quantity, but that is by design. I feel like the reason so much mediocre media gets away with its mediocrity—and gets widely made and funded further—is that people don’t fully pay attention to it as they consume it. This condensed quote from a podcast episode the Hollywood Reporter did with Justine Bateman shows that streaming services know this too:

“I’ve heard from showrunners who are given notes from the streamers that, ‘This isn’t second screen enough.’ Meaning, the viewer’s primary screen is their phone and the laptop and they don’t want anything on your show to distract them from their primary screen because if they get distracted, they might look up, be confused, and go turn it off. I heard somebody use this term before: They want a ‘visual muzak.’”

My hunch is that, if I force myself to pay attention to what I am listening to or watching, I will be far less likely to let in things that my brain considers uninteresting or boring or just plain bad art. I already see this happen when I read: As opposed to background-watching or listening to something, you cannot read while doing anything that requires you to use your eyes and hands, so you automatically end up paying more attention to what you are consuming. As a result, I abandon books I find mediocre way more often than I turn off a mediocre film I am playing in the background while vacuuming or folding my laundry.

I am what I consume. I am also how I consume. And this is true in case of all input—voluntary and involuntary. I cannot do much about involuntary input by definition, but when it comes to the voluntary kind, I can be more mindful of what I feed my brain and body and how I go about doing it.

Godspeed.

Footnotes

- While this does not mean that I have a podcast on every time I run or listen to music every time I shower, this auditory static is increasingly more present than absent in my daily life. ↩︎

- This is the video in its entirety and this is the chapter on social media. ↩︎

- My explanation is very crude. For anyone who wants to dig deeper, this study conducted by researchers at Ruhr University Bochum establishes a firm link between social media usage and materialism. While they focus on social media, it is not much of a stretch to imagine other digital media being linked to materialism and subsequent overconsumption as well. ↩︎

- Don’t knock my handwriting. ↩︎

- Easy. I already put my LinkedIn account on hibernate mode, I don’t use Goodreads except to keep track my reading list, and I am not on any other social media. ↩︎

- Physical books/papers/articles specifically, because my book cannot get a notification while I read it. I will also allow reading these on public transport. ↩︎

- I will not allow this on public transport. ↩︎

- Exception: I need earphones for work calls at the office to avoid disturbing those around me.

I can hold my phone up to my ear to make or receive calls, or to listen to voice messages.

Music/podcasts can be listened to out loud when I am at home.

I often use my AirPods to protect my ears from cold winds. I already bought some earplugs as a replacement. If they don’t suit me, I can just drain the battery of my AirPods and turn them into expensive ear plugs. Cue the “sometimes my genius is almost frightening” meme. ↩︎ - This will be challenging. My long-distance fiancé and I video call just before I sleep, so I am usually in bed during these calls. I will have to make it a habit of getting up and keeping my phone away before I sleep. ↩︎

- No calls either. Conversation is okay if it is in person (e.g., at the lunch table at work).

Exception: My flatmate and I pick a show together and watch an episode of it on the days we dine together. It’s our thing. I will permit myself that. ↩︎ - This is going to be the toughest one and the one I am most likely to go back on once my self-experiment is over. ↩︎

- Imagine an hour-long run on the treadmill with nothing to look at but the sky outside the window and nothing to accompany you but your own thoughts. ↩︎

Leave a comment